AI Adoption Starts With the First Safe Prompt

Why most AI rollouts stall and how to get across the chasm to the early majority.

Table of contents

AI adoption starts with the first safe prompt, not the first training session

I keep finding myself back at the same model.

Last year, I gave a talk at Testing Assembly 2025 about metrics adoption. The pattern I described was familiar to anyone who's tried to introduce measurement into teams: everyone agrees metrics are useful, but people are too scared to actually start. What worked wasn't training or dashboards. It was finding what I called "experimenters", early majority members I mentored in analysis and storytelling with data, who then created social proof among their peers. Once other project managers outside the original project heard good things from people they trusted, they wanted similar metrics for themselves. That spread would never have happened through training alone. It happened because a peer succeeded visibly.

Now I'm watching a variation of the same pattern play out with AI, and this time, the psychological barriers are even higher.

I lead teams of testers in a large enterprise environment, and for the past several months I've had a front-row seat to an AI rollout that followed every best practice, and still stalled. What I eventually realized is that we hadn't discovered something new. We'd forgotten the first step. Everyone is talking about the second and third steps of AI adoption, prompting techniques, advanced workflows, agentic use cases, but you never get there if you skip the one that comes before all of them.

And the data suggests this isn't just my team's problem. According to Gallup's 2025 workforce survey, only about 12% of employees use AI daily at work. PwC's numbers are slightly higher at 19% for office workers. Even the most generous estimates put regular weekly usage at 20–30%. The majority of knowledge workers are still occasional users or non-users. If you map this to the diffusion of innovation model, we've captured the early adopters, but the early majority hasn't crossed over yet. We're stuck at the chasm.

The question I keep coming back to is: what gets people across?

We got the dream tool. Nobody touched it.

For a long time, my team talked about how useful AI would be in our testing work. The answer from the organization was always the same: security concerns, IP risks, compliance questions. AI sounded exciting but distant.

Then we got Atlassian's Rovo, AI built directly into Jira and Confluence. It could see our issues, features, and history. It even allowed us to create simple agents out of the box. You could open a story you were testing and just start chatting with it. For a tester, this was close to a dream scenario. And suddenly, every concern about data leakage and security was addressed. The tool was inside our existing ecosystem.

I was the first to start using it. I built agents for testing workflows, shared them with the team, ran sessions to show what worked and where the tool still struggled. I tried to be honest about both.

The reactions were positive. People nodded. They said it looked useful. Several said they'd try it the next day.

The next day, nobody had. And the day after that, the same. For almost four months, the tool existed in a strange limbo: appreciated in theory, ignored in practice.

Why training wasn't enough

Here's what I've come to understand, partly from this experience and partly from digging into research on organizational change: training assumes people only lack knowledge. But with AI, the gaps are different.

When someone sits through a demo of an AI tool, they're not just processing information about features and prompts. They're running a quiet internal calculation: What does this mean for my role? Am I training my replacement? What if I ask something stupid and the answer exposes how little I understand? What if I rely on it and the output is wrong, who's accountable then?

This maps directly to what psychologists call identity threat. Self-Determination Theory, the framework developed by Ryan and Deci, tells us that motivation depends on three things: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. AI can feel like it threatens all three at once — your autonomy shrinks if the tool dictates the workflow, your sense of competence wobbles when you're suddenly a beginner again, and your relatedness to the team becomes uncertain when you're not sure what your craft is worth anymore.

No amount of training addresses this. You can't PowerPoint someone out of an identity crisis.

There's another layer too. Research on algorithm aversion shows that people judge algorithmic errors far more harshly than human errors. Once someone sees an AI produce a bad output, even once, trust drops disproportionately. My team hadn't even used the tool yet, but they'd absorbed enough stories about AI hallucinations and mistakes to arrive pre-skeptical. The trust debt existed before the first interaction.

What actually happened

The shift didn't come from a better agent or another training session.

Over time, through one-on-one conversations, I had built up enough shared experience with one of my onshore testers, someone who's naturally curious and easy to get excited about new things. I knew from my metrics adoption experience that I needed a champion, someone other than me to make it feel real. I was perhaps overthinking the timing, trying to set the stage perfectly. But he moved faster than I planned.

In one of our daily meetings, he offered to show something quickly. The demo was messy, there were hiccups, the usual "demo effect," and a fair amount of laughter. He showed a few things the agent had done well and poked fun at where it got confused. It wasn't a presentation so much as someone showing a funny text exchange.

Then he did something I hadn't planned for: he asked one of the other testers to open her screen and try the agent on a feature she'd worked on. She hesitated but shared her screen, opened the feature, and opened the agent. And then she froze. She didn't know what to type.

Someone suggested, half-jokingly: "Just say hello."

She did.

The agent responded and we read the answer together, talking about what seemed useful, what looked questionable, and what she could ask next. She tried another prompt and we discussed that one too.

It wasn't a long session and nothing dramatic happened, but the atmosphere was relaxed, almost playful. Nobody expected perfection. It felt like a shared experiment, not a test of anyone's competence.

Two days later, everything was different

In the next daily, I asked a simple follow-up after each person described their work: "Did anyone use Rovo while doing that?"

Over half the team said yes. Finally!

And this time the answers weren't polite promises. They were concrete: one person said the agent had surfaced two old defects related to her investigation. Another said it helped find everyone who had previously worked on the issue. Someone else described how it generated test cases she used nearly as-is. A fourth mentioned that the customer had been particularly happy in a review of AI-assisted test cases.

When I checked the usage metrics after that week, the agent had gone from one or two active users to five or six daily users, with over a hundred chats per week.

Nothing in the tool had changed. Only the social situation had.

Why this keeps happening

The more I read, the more I recognize the mechanism. Amy Edmondson's work on psychological safety describes exactly what I observed: people will only engage in learning behaviors, asking for help, admitting uncertainty, experimenting with new practices, when they believe the interpersonal risk is low.

Using AI for the first time is an interpersonal risk. You're exposing your thinking process. You're showing that you don't know how to talk to a machine. You might ask a "dumb" question. You might get a dumb answer. In a team setting, that feels vulnerable.

What happened in that daily meeting wasn't training. It was the creation of psychological safety around a specific act: typing something into a prompt. The demo was imperfect, which helped. The laughter was genuine, which helped more. Nobody was graded. And the first prompt was literally just "hello", the lowest possible bar, offered with warmth rather than instruction.

This is also why the pattern rhymes with my metrics experience, even though the mechanisms were slightly different. With metrics, it was peer success that created the pull, experimenters who visibly benefited, which made others want the same thing. With AI, it was a safe first interaction that broke the paralysis. In both cases, formal training moved nothing. In both cases, what mattered was a social moment: either seeing a peer succeed, or trying something together without judgment. The common thread is that adoption spreads through people, not through programs.

It's the diffusion of innovation model playing out at the smallest possible scale. The tool had an early adopter (me), but early adopters are often too far ahead to pull others along. What was needed was an early majority moment, and those moments are social, not technical. They require not a champion who's an expert, but a peer who's visibly figuring it out.

What this means for AI rollouts

Most organizations treat AI adoption like a software rollout: provide access, run training, share documentation, track adoption metrics, escalate when numbers are low. Many are doubling down on this approach right now, more workshops, better prompt guides, fancier demos, and wondering why the numbers barely move. They're optimizing the second and third steps while skipping the first.

But AI isn't a new button in the interface. It's a new kind of collaborator that interacts with people's professional judgment, competence, and identity. The first interaction feels social, not technical. And in social situations, safety matters more than instructions.

If I were starting fresh with a new team tomorrow, and I will be, because full adoption at scale is nowhere near realized, here's what I'd do from day one. This is also what I'm actively continuing with the teams I already work with:

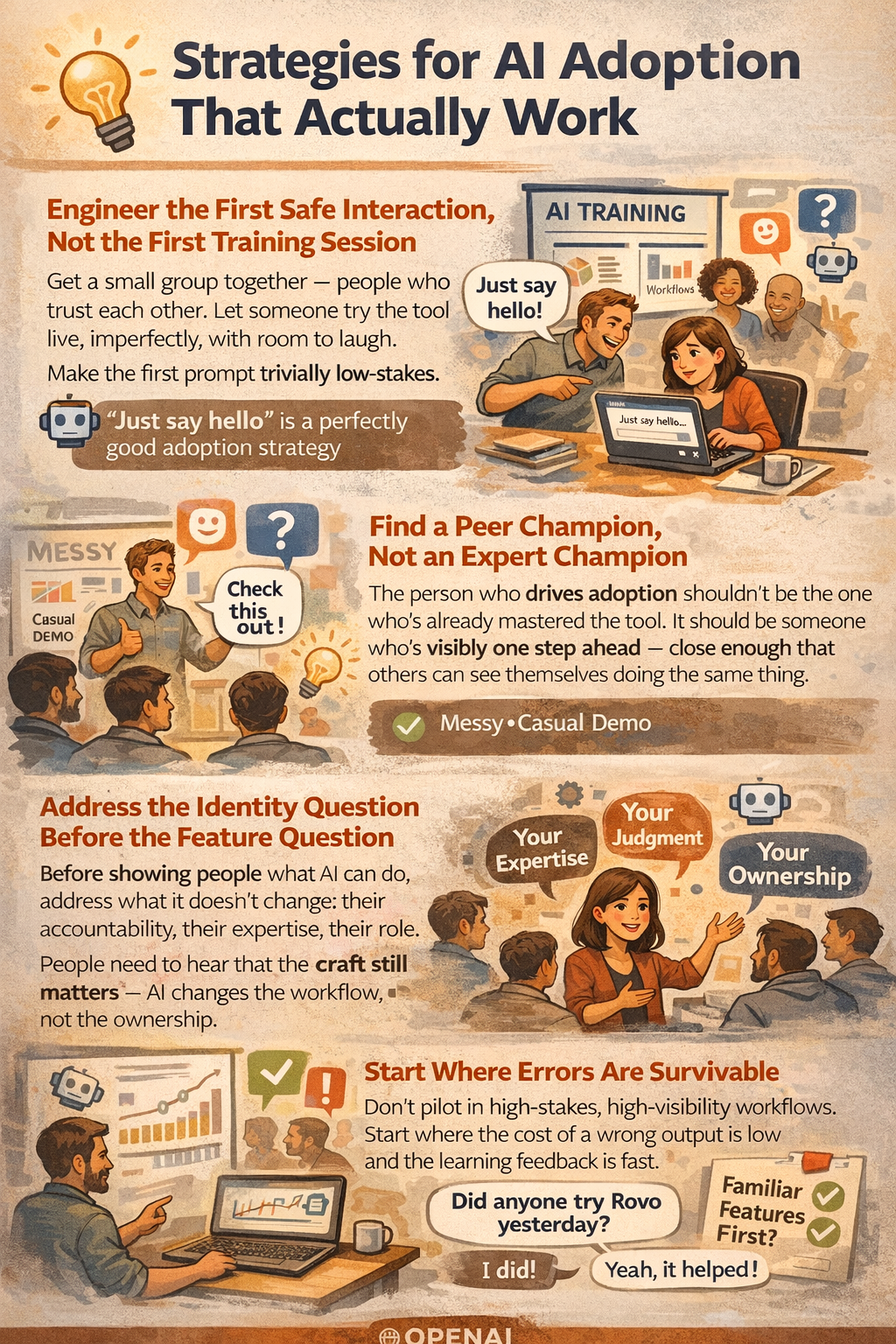

Engineer the first safe interaction, not the first training session. Get a small group together, people who trust each other. Let someone try the tool live, imperfectly, with room to laugh. Make the first prompt trivially low-stakes. "Just say hello" is a perfectly good adoption strategy.

Find a peer champion, not an expert champion. The person who drives adoption shouldn't be the one who's already mastered the tool. It should be someone who's visibly one step ahead, close enough that others can see themselves doing the same thing. My champion was effective precisely because his demo was messy.

Address the identity question before the feature question. Before showing people what AI can do, address what it doesn't change: their accountability, their expertise, their role. People need to hear that the craft still matters, AI changes the workflow, not the ownership.

Start where errors are survivable. Don't pilot in high-stakes, high-visibility workflows. Start where the cost of a wrong output is low and the learning feedback is fast. My testers used Rovo on familiar features first, territory where they could immediately judge the output quality.

Make usage visible and normal. The single most effective thing I did was asking, in every daily, "Did anyone use Rovo while doing that?" Not as an audit, as a casual question that made AI usage part of the normal conversation. Once three people said yes in front of each other, it became unremarkable.

The uncomfortable simplicity of it

Four months of access, training, and documentation moved nothing. One short, slightly chaotic, but psychologically safe interaction changed everything.

I keep coming back to this because it feels both obvious and underappreciated. The research supports it. My experience confirms it, across metrics, across AI, and across different teams. And yet most AI rollout plans I see are still structured as if information is the bottleneck.

It isn't. Safety is.

With 80% or more of knowledge workers still not using AI regularly, we're clearly still early. The early adopters are in. The question is how to bring everyone else along. I don't think the answer is more training. I think it's more moments like the one in that daily meeting, small, human, imperfect, and safe.

I have plenty of other teams to test this thesis on. I'll come back and share whether the pattern holds or breaks. But so far, the signal is consistent.

Sometimes transformation doesn't begin with a strategy, a roadmap, or a training program. Sometimes it begins with someone staring at a blank prompt, and another person saying:

"Just say hello."